WAR IS MY BUSINESS

WAR IS MY BUSINESS

2.4

The Purpose of Warfare

"Scaling the Wall With A Little Help"

SFC Sieger Hartgers

Saudia Arabia, 1991

If we desire to avoid insult, we must be able to repel it; if we desire to secure peace, one of the most powerful instruments of our rising power, it must be known, that we are at all times ready for War.

-George Washington’s Annual Address to Congress - December 3rd, 1793

Humans are a social species. Our ancestors evolved alongside other species on a planet with finite resources. There is not enough organic matter, plant or animal, to sustain every creature. Every species competes against other species and amongst themselves for these dwindling resources. Life on this planet has evolved to survive; it had to because there isn’t enough for every living thing to thrive. Life has learned to consume other species, as relying only on gathering nutrition and energy from our organic, non-living matter is limiting. It was a new attack vector for life to thrive, or in business parlance, an untapped market resource ripe for exploitation. Life no longer had to be concerned with only limited access to resources but becoming a resource for other species. Humanity’s ancestors evolved to consume other life.

If we harken back to Chapter 1.3: Life and Evolution, I used NASA’s definition of life as “a self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution.” Darwinian evolution requires species to survive and pass their genes to future generations. It doesn’t matter that some die, only that some live long enough so that the species can produce offspring. Some species produce numerous offspring as often as possible, and even though most die off, some survive to produce even more, quantity over quality, in a sense. Other species have fewer offspring but invest more effort and resources into rearing them, protecting them into adulthood when they can have their own offspring, an inverse of quality over quantity. Humanity’s ancestors evolved along this latter path.

Most species on this planet live independently. Of these independent animal species, they generally search for food and water, find mates, produce offspring, and carry on like this until their eventual deaths. For some animals, however, they also evolved to develop ingrained social hierarchies with those within their own species, with kin and others with common goals. There are less than 3,000 social species on this planet, and humanity is one of them.

With limited resources, few offspring, and strong social collectives, many species are forced to contend with threats to their lives or the resources of the area they happen to occupy. These species can often assess whether fleeing or fighting off the aggressors is the best strategy for survival. Humanity developed along this path, being able to weigh between short-term and long-term survival strategies.

Some social species utilized competitive sexual selection amongst their males. These males are physically larger, stronger, and more aggressive than their female counterparts so that they can compete against each other for the interests of the females. A female would be interested in such a male because the male would provide the strength and aggression needed to protect kin, secure resources, and generally ensure the long-term survival of the social group. As mentioned in Chapter 2.0: On Violence, this is the course humanity took. We see throughout all human cultures that males are disproportionately prone to aggression and physically more capable in that aspect.

Those social species who fight for their resources have evolved to work cooperatively. Their survival was predicated on taking and holding resources. Many of these species also used tools within their environment to compensate for individual weaknesses and increase their effectiveness in applying violence. Humanity, therefore, evolved to be both violent and employ tools for violence.

Where am I going with this talk of evolutionary paths and survival strategies? Simply put, war is an evolutionary inevitability of our species. Organized conflict isn’t the norm of most species, but it is for the rare few creatures on this earth. Homo Sapiens, humanity, is such a species because:

- Resources are finite: our ancestors’ survival required them.

- Struggle for survival is integral to evolution: our ancestors had to adapt.

- Through adaptation over time, collaborative support provided an advantage: our ancestors evolved complex social groups to survive within an inhospitable world.

- Through long-term planning, people can work together to defeat threats and protect the social group: our ancestors learned to organize themselves for conflict against threats.

- Implements of the natural world could offset natural weaknesses: our ancestors employed and developed tools.

- A species with larger and more aggressive males than females evolved to engage in competitive sexual selection: our male ancestors became more aggressive to provide resources and security to earn that selection.

- When a social creature is weak in isolation but strong collectively while also perpetually on the hunt for limited resources, there can be infighting within their species: our ancestors became tribalistic and territorial.

- Because a close-knit social group will view outsiders with suspicion if friction can’t be avoided, then violence can erupt: humanity often resorts to violence in one form or another during disputes.

- Since evolution is the struggle of life despite death, and conflict is full of death, organized conflict evolves over time: to survive, our ancestors developed larger social organizations, adapted their implements of violence, and improved upon their communication in tactics and strategy.

For all these aforementioned points, organized conflict was inevitable for our species. The current political landscape, the technological innovations we have, and the foundation of the human condition - all of it - are based on humanity’s evolved survival methods, of which organized conflict has become a defining factor. But conflict is just that, a factor.

Conflict helps solve the problem of survival through the tool of violence, but there are other tools. We mentioned this as much in Chapter 2.0: On Violence when we mentioned that violence was becoming less vital as a tool to solve our survival problems. For example, human cooperation is another tool we use to survive. On the one hand, it increased the likelihood of survival when faced with violence through the use of cooperative violence to counter it, meaning organized conflict. On the other hand, cooperation also provided survival solutions through non-violent methods. Within a cooperative group, some could focus on providing security, while others could focus on agriculture and infrastructure development. It allowed a few to protect all within the group while the others could provide for all. Cooperation between groups through exchanging resources necessary for survival could circumvent the need for violence that otherwise would have resulted. But violence has never left our species and is the fundamental crux of humanity in our struggle to survive. We must understand this nature if we wish to control it effectively.

For the remainder of this chapter, we will discuss warfare's historical and contemporary purpose for our species and how it serves as a tool alongside or despite other survival tools. During these discussions on the purpose of warfare, the other survival tools, especially business as a natural evolution of human cooperation, will be compared and contrasted. By the end, you will see that, though the ways and means may differ, the ends are ultimately the same - some aspect of a survival strategy.

Purpose of War

Purpose of War

And through all this welter of change and development your mission remains fixed, determined, inviolable. It is to win our wars. Everything else in your professional career is but corollary to this vital dedication. All other public purposes, all other public projects, all other public needs, great or small, will find others for their accomplishment; but you are the ones who are trained to fight. Yours is the profession of arms, the will to win, the sure knowledge that in war there is no substitute for victory, that if you lose, the Nation will be destroyed, that the very obsession of your public service must be Duty, Honor, Country.

-Douglas MacArthur’s Speech to the Corps of Cadets at West Point - May 12th, 1962

Now before we begin we must discuss what we mean by “war.” War has its more contemporary concept as a formal declaration of open hostilities between two or more groups, especially between internationally recognized governments. Another view is that war is simply a state of open hostilities regardless of a formal declaration. A conflict like the one between the United States and Vietnam was not a war in the first sense. The United States Congress did not declare a state of war between America and North Vietnam. In the second sense, however, there was war as America, its allies, and South Vietnam were in open conflict with the North Vietnamese and Vietcong.

For War Is My Business, naturally, we use the second interpretation as this is our area of study; the theories, principles, and tenets learned through organized conflict. I don’t necessarily care whether the conflict was decreed by formality, except when that formality impacts the nature of the conflict. In turn, for groups, I don’t only look toward political bodies; such as nations, city-states, kingdoms, chiefdoms, and tribes, but also non-political entities to include criminal associations; such as gangs and cartels, or transnational militants; like private military companies (mercenaries) and terrorist organizations.

From the business perspective, while business is generally viewed as commercial activities between companies and customers, business-to-business and business-to-consumer, it also can be viewed as any cooperative trade or exchange between groups and related activities. For example, nations agreeing to exchange natural resources for cash or military aid, a company building factories overseas to tap new markets and reduce costs, and cartels killing rivals and smuggling narcotics across borders. It's all just business in a certain sense.

So, War Is My Business as a whole, and for this chapter in particular, we use the more open interpretation of the words “war” and “business.” A soldier of a nation, a guerrilla in a militia, or a gangster in a gang can all be viewed as engaging and supporting the activity of war - organized conflict - just as a national leader in a trade deal, a company running adverts, and a drug dealer peddling meth can all be viewed as engaging and supporting the activity of business - facilitating cooperative exchange.

Now that these terms have been clarified, we will look back throughout the history of warfare to see what it has provided to its participants. The reasons they sought to engage in it, and how it supported their ultimate goals. But first, we begin with its role in prehistory, so that we may understand the origins of this nature.

Earliest Forms of Organized Conflict

Earliest Forms of Organized Conflict

In contemporary times, we see that all cultures on our planet have engaged in the application of violence in one form or another. Firearms are ubiquitous, even amongst developing countries, but looking at the world's isolated tribes; such as those on North Sentinel Island and the Amazonian tribes, they too have bows, spears, blow darts, and bludgeoning devices. Even if they used these devices primarily for hunting prey, the handful of inquisitive or unfortunate explorers or missionaries who ventured too close to their lands found themselves harassed by arrows; some resulting in their deaths.

When Europeans started arriving in the Americas, they recorded and discussed the nature of conflict and weaponry amongst the native peoples. At first, Mesoamericans, such as the Aztecs and their conquests of smaller tribes, then the tribes of North and South America as European colonialists started establishing themselves and witnessing native interactions. Similar capabilities to those tribes we see today, but whose weapons have changed to reflect the nature of their local environments.

North Sentinel Island men with bows. Sometimes know for killing outsiders that get too close; including missionary John Allen Chau. Screen capture taken from "Man in Search of Man."

Cave painting depicting a fight between archers. Transcribed from a cave in Morella la Vella, Spain. Wikicommons

But how far back can we go to get evidence of human-on-human conflict? Cave paintings in Spain, dating back to 20,000 BC, show a group of men fighting each other with bows. While the image of men fighting each other doesn’t necessarily mean that the men depicted actually fought or that the men in the painting reflected real people known to the artist, which would make it a fictional event, only that in the mind of the artist we can see that the concept of human conflict was possible.

It would make sense that the earliest forms of war would reflect, in some form, organized hunting. Hunting allowed humans to use their capacity to communicate and coordinate to take down large beasts or flighty prey animals. The cave painting, showing bow-equipped men running or lunging in a somewhat chaotic battle, leaves much to interpretation. It could represent two groups of men staying low to the ground, lunging to avoid being hit by their adversaries, and presenting themselves as smaller targets. Or it could be representative of dashing in and out of a fight in a hit-and-run style of guerrilla combat.

Regardless of what we can interpret about complex human dynamics from a cave painting, we can determine that humans fighting other humans with weapons was probable, even if it was a rare event. Indeed, for the bulk of the 180,000 years of homo sapiens development, our populations were relatively small, with vast stretches of Earth that could be utilized by our ancestors. It would make logical sense that, if it could be avoided, hunter-gatherer tribes would simply move on to new areas than risk fighting.

Naturally, other than resources, as discussed in Chapter 2.0: On Violence, humans would also fight for access to females and as revenge for previous transgressions. Indeed, it is possible that the painting could have been a real event that transpired because one group of men had little to no females left in their group and attacked the other group of men to then abscond with their females. Or it could be that one group stole the kill off of the other group or killed a member of their tribe, and this battle is one of revenge. I bring this up to say that early battles between humans were probably not related to purely defeating other groups of humans to ensure long-term survivability and were more likely short-term emotional responses to slights. Avoiding fighting was still the best form of long-term survival for a group, so unless short-term necessity required it, we wouldn’t see an extensive organized conflict between humans until the environment changed which would necessitate this outlook.

It is possible that the environmental change that compelled humans to engage more often in organized conflict out of necessity was related to a shift from hunter-gathering to other societal structures. Hunter-gatherers would travel where the animals were; they were nomadic and not vested in any particular area other than through their familiarity with the terrain.

- Some groups began tilling the land, planting crops, watering and fighting off pests, and then harvesting and storing the produce. They began to develop a sense of ownership of the land they worked on. Their survival was tied to the land they toiled, and other humans that weren’t part of the tribe were a threat to this bounty the farmers created as it turned the farmers into a target for pillaging.

- Some of these groups began domesticating animals and herding them to pastures. They had to care for them, maintain control of their movements, fight off predators, and were connected to their animals from birth through the milking of their mothers and their eventual slaughter for meat. Their survival was tied to the health and abundance of the herd, and other humans were a threat to the herdsman's prosperity through theft and poaching of their animals.

Robert L. Connell, in his book Of Arms and Men: A History of War, Weapons, and Aggression, postulated that this shift to warfare being more prevalent was because humans started developing a sense of ownership to land and animals in this way; agriculture and husbandry. Because a group of humans’ survival was tied to a thing, they simply couldn’t avoid a fight if that thing was threatened. If you, your mate, your offspring, and your kin’s survival is predicated on crops or a herd, then you and your kin must cooperate in fighting off other humans that threaten it. Organized human conflict, therefore, became more of an inevitability when humans developed a sense of ownership, treating land and animals as property.

It may have begun when nomads - pastoralists or possibly advanced hunter-gatherers - having learned to steal from each other, descended on the fertile valleys and oases of the agriculturalists to rob his surpluses. Women and revenge, the traditional motivators, presumably still played a role in these depredations, but it was this new factor, property which provided impetus that had been missing previously… Having suffered at the hands of the interloper, agrarian communities gradually learned to defend themselves. In doing so they discovered that their more efficient economic systems imparted certain advantages in terms of time and available resources to be expended on martial activities.

(Of Arms and Men, 31)

As people could generate their own food, societies could increase in size, and individuals could specialize in particular professions; for example, farmers, carpenters, and warriors. New technologies allowed for more efficient human effort in each profession, which advanced societies by leaps and bounds. Basically, once humans developed beyond simple hunter-gatherers, societies could and did expand and advance at an alarming rate not seen in other species. Before complex philosophical discussions over the nature of our existence on this planet in our earliest years, our species probably viewed conflict amongst humans as a natural occurrence. No more different than the struggles associated with natural disasters, attacks by predators, starvation, and basic human health considerations, like illness and childbirth complications. Things could be emotionally taxing, and we could be fearful of their potential occurrence and prepare for them, but violence alongside these other concerns was just a way of life.

As our species continued to develop and understand the natural world with a little more complexity, as we do now, our ancestors probably started assigning greater significance to warfare as a unique aspect of the human condition. As a unique social activity comparable to agricultural development, bartering, sexual selection, games, and governance. We had to be cognizant of our situations, wary of potential threats, and prepared to respond to those threats before or after they became apparent.

Now, this is pure speculation. Prehistoric humans have only given us evidence of their existence through their bones, tools, and simplistic paintings. They had no way of communicating their perspectives on human conflict to us in the future. We are left with only speculation, deconstructing our history and psychology, and comparing and contrasting humans against other species in order to find a concept for early homo sapiens conflict that is logical and reasonable. But we will leave prehistory to the anthropologists.

War Is My Business is more concerned about our history, and the aspects of our story as a species that are recorded in some fashion. Though homo sapiens have been around for about 180,000 years, we have only had written language for a little more than 5,000. This gives us a window to look back into our various cultures. Each culture has its own perspective on the nature of conflict, which changes over time and with each individual based on their understanding of the natural world. We are concerned about how they viewed human conflict in relation to 1) the society, 2) the political governing body, 3) the individual, and 4) the natural world itself. Knowing how they viewed the environment around them, we can then take those theories, principles, and tenets for warfare from their perspective, translate them for modern times, and then compare, contrast, and apply them to other human endeavors, such as business. Because although our ancestors sometimes viewed warfare as a unique category of human social activity, it is nonetheless a social activity, more similar than different from the others.

Political theorist Michael L. Walzer holds this viewpoint of war being a comparable social activity in his book, Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations when he stated:

Here the case is the same as with other human activities (politics and commerce, for example). It's not what people do, the physical motions they go through, that are crucial, but the institutions, practices, conventions, that they make. Hence the social and historical conditions that “modify” war are not to be considered as accidental or external to war itself, for war is a social creation. What is war and what is not war is in fact something that people decide. (Just and Unjust War, 24)

The ways and means of warfare are a special consideration when we determine what is “war” and “business.” But it is those ways and means that we refer to in order to differentiate between these two social activities, and it isn’t necessarily a clean-cut distinction. Arms manufacturers, defense contractors, private military corporations, and mercenaries use the ways and means of both war and business in various capacities. War and business are different in that they use different ways and means, but war and business are the same in that they are social activities that include doctrinal ways of carrying out tasks, organizational structures and hierarchies, training regimes, material needs, leadership and educational development programs, personnel requirements, and facilities to conduct activities. War is more similar to business, as is any social activity, because all human social activities are created by humans and share common fundamental structures. Humans aren’t as complex as we like to think we are, and our “social creations,” as Walzer calls them, follow particular structures familiar to humans.

So, now we look back at our history. We look to military leaders and strategists of the past and present to see how they viewed the nature of warfare in order to learn something about ourselves vicariously through their experiences and perspectives. From here, we see the purpose of warfare from their cultures, time periods, and assessments of their situations that lead them to decide to wage war.

A Historical Perspective On The Purpose of Warfare

A Historical Perspective On The Purpose of Warfare

The following is by no means close to being a complete list of perspectives from all of the potential eras and cultures, or even that each individual somehow shares a common consensus on warfare with their own contemporaries. There will be some inherent bias on who was selected based on the importance of their contribution to the study of military theory and the quality of the discussion they had on the topic of the purpose of warfare. We endeavor, however, to provide enough of a perspective on the topic from these different theorists through both time and space of human history, in order to develop a coherent understanding of warfare’s place within human society.

The theorists who we will be quoting will be ordered based on their chronological appearance throughout history: from ancient to the present. Since these theorists come from around the world, by necessity, some quotes will be translations of primary source documentation.

Jiang Ziya

Six Secret Teachings (Liu Tao)

11th Century BC - Zhou Dynasty China

Jiang Ziya, uknown artist depiction. From Wikimedia Commons

Western Zhou Dynasty. From Wikimedia Commons

During the time of ancient China’s Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BC), Jiang Ziya served as counselor and strategist for the small state of Zhou. While assisting King Wen and then King Wu of Zhou, he provided the needed guidance that would eventually lead to the slow collapse of the Shang and the rise of the Zhou. This would lead to the next dynastic period of the Zhou (1045-256 BC), generally attributed to the strategies employed by Jiang Ziya.

What you need to know about the environment that the Zhou found themselves in was that Zhou was a relatively small and weak state to the west of the Shang. The Shang were so powerful that they could, allegedly, field armies larger than the population of Zhou itself. In the eyes of King Wen of Zhou, however, the decadence and abuse of the Shang compelled him to do something to combat it. To succeed, he would need a comprehensive plan and a strategist to develop it. This is where Jiang Ziya enters the scene to provide his guidance on when to make the decision to go to war.

You should cultivate your Virtue, submit to the guidance of Worthy men, extend beneficence to the people, and observe the Tao of Heaven. If there are no ill omens in the Tao of Heaven, you cannot initiate the movement [to revolt]. If there are no misfortunes in the Tao of Man, your planning cannot precede them. You must first see Heavenly signs and moreover witness human misfortune, and only then can you make plans. You must look at the Shang king’s yang aspects [his government], and moreover his yin side [personal deportment], and only then will you know his emotions…

Now there is the case of Shang, where the people muddle and confuse each other. Mixed up and extravagant, their love of pleasure and sex is endless. This is the sign of a doomed state. I have observed their fields - weeds and grass overwhelm the crops. I have observed their officials - they are violent, perverse, inhumane, and evil. They overthrow the laws and make chaos of the punishments. Neither the upper nor lower ranks have awakened to this state of affairs. It is time for their state to perish.

(Six Secret Teachings - 53-54)

It was the belief of Jiang Ziya that the purpose of war was to correct a wrong within society. The government served to provide guidance and support to the people’s lives and acted as a conduit between heavenly forces and the terrestrial physical world of nature. This was part of a common belief in the harmonious balance of things; yin and yang, heaven and earth, government and governed, civil and martial, men and women, etc., of which balance was necessary or problems would arise for society.

Indeed, these concepts of balance within the natural world, as well as some of the rites conducted to help mold an individual into a virtuous person and produce harmony would later coalesce into Lao Tzu’s perspectives on Taoism and in the teachings of Confucius. Submission to the natural world in these ways was seen as necessary to gain an auspicious fortune in one’s favor. As we mentioned earlier in Chapter 1.5: The Human Domain, where I quoted and discussed this very quote from the Six Secret Teachings, these rites are an extension of the cultural norms of their people for their time. Necessary for its time, though maybe not so much for us in the 21st Century, nonetheless, these religious concepts permeated discussions of a military nature. The Shang were seen as corrupt. They took advantage of their positions of power to pursue a life of decadence and oppressed the people with unfair taxes and excessive extravagant work projects that did not provide a benefit to the people.

In the first paragraph quoted, Jiang Ziya discusses when one should not go to war, or in their case revolt against the Shang. The Tao [the way] of Heaven and Men, if they are harmonious, with no ills or misfortunes, then the Zhou should not seek conflict. Implying that there is no need to engage in war because if things are good, then war serves no purpose. In the second paragraph, however, he goes on to state that, in fact, things are not harmonious within the Shang, and they are failing in their duties to the people. He notes that because the upper and lower ranks, the various levels of government, are unaware of the problems facing the people, the state of Shang is bound to fail as a result. This also might imply that, if the government was aware of the problems, then the Shang’s situation may be salvageable and that war could be avoided. However, these things were not the case, or at least that is how it was written, and thus the state of Zhou under King Wen and then King Wu, with the support of Jiang Ziya began their plan to overthrow the Shang.

The small state of Zhou would first need to practice what it preached, in a sense, cultivate its leadership, and fill offices with men of Virtue and Worth. They supported agriculture and commerce within their own territory while developing their military prowess by fighting barbarians on the periphery of China. The Zhou would seek to weaken their main adversary by conquering the smaller states allied with them, all the time keeping up appearances of being a subjugated vassal state to the Shang.

In contemporary parlance, the Zhou wined and dined the Shang while removing the Shang’s coalition of friends; Zhou got stronger while Shang got weaker. The Zhou played the long game up until the point when the Shang were alone and internally weak. King Wu, along with Jiang Ziya, marched upon the Shang capital and many of the Shang’s soldiers; dejected and demoralized, defected to the Zhou, and the collapse of the Shang Dynasty followed.

The purpose of war, therefore, according to Jiang Ziya’s Six Secret Teachings was to bring harmony back to the world. The way of things, the Tao, in turn, would manifest this balance in the prosperity of the people, their land, and the state itself. The Zhou pursued war to restore harmony in the natural world, and by doing so benefited the people.

Ssu-ma Jang-chu

The Methods of the Minister of War (Ssu-ma fa)

11th Century to 4th Century BC - State of Qi, China

Collector's edition of the Ssu-ma fa. No artist depictions of Ssu-ma Jang-Chu (Sima Rangju). Taken from the liveauctioneers.com

The extent of the State of Qi's territory (in yellow) before the end of the Warring States when the State of Qin established the Qin Empire. From Wikimedia Commons

The state of Qi, modern-day Shandong province of China, had been known for upholding strong martial principles throughout antiquity. This work, the Ssu-ma fa, can’t necessarily be tied to a specific individual, and may very well have been a compilation of writings of numerous individuals associated with the title of Ssu-ma. Ssu-ma [lit. Officer in charge of horses] was the title for the state’s minister of war, and while much of what was written has been lost; only 5 of the 155 chapters of this treatise remain, the bulk of the concepts written about could be attributed to the Ssu-ma Jang-chu. As a result, there isn’t really a time period that pinpoints the publication of this work other than a range of centuries from the establishment of the Zhou Dynasty (1045 BC) to the later Warring States period (403 - 221 BC). However, since King Ching of Qi (547 - 490 BC) is said to have employed the teachings in the reconquest of lands lost to the Qin, we could say the bulk of the Ssu-ma fa, in its earlier forms of noted concepts and principles, was available during his reign.

The very first passage of the Ssu-ma fa states:

In antiquity, taking benevolence as the foundation and employing righteousness to govern constituted “uprightness.” However, when uprightness failed to attain the desired [moral and political] objectives, [they resorted to] authority [ch’uan]. Authority comes from warfare, not from harmony among men. For this reason if one must kill men to give peace to the people, then killing is permissible. If one must attack a state out of love for their people, then attacking is permissible. If one must stop war with war, although it is war it is permissible. Thus benevolence is loved; righteousness is willingly submitted to; wisdom is relied on; courage is embraced; and credibility is trusted. Within, [the government] gains the love of the people, the means by which it can be preserved. Outside, it acquires awesomeness, the means by which it can wage war. (Seven Military Classics of Ancient China, 126)

This passage harkens back to the time of Jiang Ziya, King Wen, and King Wu of Zhou, and potentially earlier to the possibly mythical Xia Dynasty and the earlier Sage Emperors. In the same way that Jiang Ziya saw war as a means to correct wrongness in the harmony of man through the ousting of those that caused the wrongness, we have that justification here a few hundred years later. Killing, attacking, and waging war are seen as evils but necessary when faced with the greater evil of disharmony within society and the suffering it can cause. A leader shouldn’t engage in conflict out of personal gain but as the rightful duty of a just and virtuous ruler.

The Ssu-ma fa acknowledges that society is best served when those in power have displayed “uprightness.” Indeed, the beginning of dynasties, like the Zhou, were generally peaceful and productive for a time, the people were generally happy, and there was little need for military activity, except on the periphery of the empire where the barbarians were active. During relative peace, the leader must balance military necessity with the needs of the civil. For example, taking into account the seasons so that your soldiers could return in time for planting and harvesting and not working them to exhaustion was how a ruler “loved” their people.

Much of what is seen as the purpose of warfare for the Ssu-ma fa could be classified as the ethical imperative of leadership. War was to punish the unrighteous for the sake of the people and the harmony of nature, and war wasn’t even the suggested first option available to rulers. When dealing with somewhat autonomous feudal lords within the empire, it was the duty of the kings to inspect the goings-on in their lands and ensure these lords were carrying on their duties to the people in a virtuous manner. If a lord refused to rectify their transgressions against the people and against the kingdom, then it is the ruler’s duty to employ their “authority” to rally the other lords to correct it.

In the Ssu-ma fa, after having exhausted remedial peaceful efforts to fix the unvirtuous lord, it states:

Only thereafter would the Prime Minister charge the army before the feudal lords, saying, “A certain state has acted contrary to the Tao. You will participate in the rectification campaign on such a year, month, and day. On that date the army will reach the [offending] state and assemble with the Son of Heaven to apply the punishment of rectification.”

When you enter the offender’s territory, do not do violence to his gods; do not hunt his wild animals; do not destroy earthworks; do not set fire to buildings; do not cut down forests; do not take the six domesticated animals, grains, or implements. When you see their elderly or very young, return them without harming them. Even if you encounter adults, unless they engage you in combat, do not treat them as enemies. If an enemy has been wounded, provide medical attention and return him.

When they had executed the guilty, the king, together with the feudal lords, corrected and rectified [the government and customs] of the state. They raised up the Worthy, established an enlightened ruler, and corrected and restored their feudal position and obligations. (127-128)

This passage reflects the Ssu-ma fa’s position on intent for the purpose of warfare beautifully, at least when the enemy is internal to the empire itself. A problem with leadership was identified, and when administrative efforts could not correct it, they believed in a limited-scope military operation specifically to deal with the offenders. It was not the state as a whole, its people, its beliefs, and its land that needed to be punished, only its leadership and potentially the institutions the leadership established to run the state. The state would not be destroyed, only placed under new management with external guidance to create better governance institutions and promote people of merit within the state.

The purpose of war, therefore, according to Ssu-ma Jang-chu’s Ssu-ma fa, was to rectify bad governance and bring harmony back to the people. Until the Warring States period, there had been relative peace within the empire, so war was a tool to correct the bad leadership of subordinate states. The soldiers of these states may die in the process, but that is not the intent, and the suffering of war should be avoided if at all possible.

(alternative spelling: Ssu-ma Jang-chu = Sima Rangju)

Sun-Tzu

5th Century to 3rd Century BC - China

Artist depiction of Sun Tzu (Sun Wu) painting during the Qing Dynasty. From Wikimedia Commons

5th Century BC Chinese plains. Pulled from Wikimedia Commons

Just like the Ssu-ma fa, it is difficult to ascertain the exact individual to whom The Art of War was attributed. While the histories reference a Master Sun (Sun-Tzu), it isn’t exactly stated with clarity which person named Sun it is. Still, historians have noted that it is highly probable that the individual is Sun Wu. As stated in the Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yueh, it stated:

Sun-Tzu, whose name was Wu, was a native of Wu. He excelled at military strategy but dwelled in secrecy far away from civilization, so ordinary people did not know of his ability. (Seven Military Classics of Ancient China, 151)

Even if Sun Wu was the originator, it is highly likely that he developed his concepts off the backs of other works and simply refined and tailored his work to reflect his environment and audience. Additionally, it is likely that the complete work of The Art of War that we have today was not Sun Wu’s final iteration, and it is likely that it floated throughout the Sun family, being further revised by his descendants, like Sun Bin, an alleged descendant of Sun-Tzu from the late 3rd Century BC. Regardless, this treatise was an important document within Wu (modern-day Jiangsu province of China).

Sun-Tzu states:

The art of war is of vital importance to the State. It is a matter of life and death, a road either to safety or to ruin. Hence it is a subject of inquiry which can on no account be neglected… (157)

Thus one who excels at employing the military subjugates other people’s armies without engaging in battle, captures other people’s fortified cities without attacking them, and destroys other people’s states without prolonged fighting. He must fight under Heaven with the paramount aim of ‘preservation.’ Thus his weapons will not become dull, and the gains can be preserved. This is the strategy for planning offensives...(161)

The prosecution of military affairs lies in according with and [learning] in detail the enemy’s intentions. If one then focuses [his strength] toward the enemy, strikes a thousand li away, and kills their general, it is termed ‘being skillful and capable in completing military affairs.’

For this reason on the day the government mobilizes the arm, close the passes, destroy all tallies, and do not allow their emissaries to pass through. Hold intense strategic discussions in the upper hall of the temple in order to bring about the execution of affairs...(182-183)

If it is not advantageous, do not move. If objectives cannot be attained, do not employ the army. Unless endangered do not engage in warfare. The ruler cannot mobilize the army out of personal anger. The general cannot engage in battle because of personal frustration. When it is advantageous, move; when not advantageous, stop. Anger can revert to happiness, annoyance can revert to joy, but a vanquished state cannot be revived, the dead cannot be brought back to life. Thus the enlightened ruler is cautious about it, the good general respectful of it. This is the Tao for bringing security to the state and preserving the army intact. (184)

The bulk of The Art of War covers the operational and tactical-levels of military operations. The employment of forces, the utilization of spies and scouts to gather intel on enemy movements and composition, and the nature of the types of terrain and their impact on military movements and morale. Sun-Tzu does bring up a few points covering the strategic-level of war, such as the impact and handling of enemy and friendly alliances. But this treatise, for all of its importance in Chinese military history, and its cultural impact on militaries and industries worldwide, is pretty barren regarding state-level discussions, the purpose of warfare for the state, as opposed to other tools like diplomacy or economic leverage.

Indeed, it appears that for the topic of military affairs, military deployment appears to be a given decision by the ruler. The Art of War seeks to provide guidance on how best to move forward from that decision. Sun-tzu acknowledges that the study of military affairs and the employment of military forces is vital to the state. Still, instead of saying why that is the case, it is left to the reader to draw their own conclusion or simply accept as a given reality that we all know the consequences of not taking the study of warfare seriously. He further details this discussion with more practical applications of the study of war than just a philosophical reflection on the nature of war. Making assessments on enemy combat capabilities; managing military movements through banners, pendants, gongs, and drums; how to move through and employ different terrain types; how to use fire for certain effects; and the employment of spies.

The closest we can find, in the entirety of the treatise that discusses state-level interests for the purpose of war is in the very last passage quoted. He says, “Unless endangered do not engage in warfare.” It is up to the reader, or in his case, the state's governing body, to determine what criteria within the environment imply the state may actually be endangered. But the consequences of failure are the crux of the importance of the study of warfare when he says, “a vanquished state cannot be revived, the dead cannot be brought back to life. Thus the enlightened ruler is cautious about it, the good general respectful of it. This is the Tao for bringing security to the state and preserving the army intact.”

He is less concerned about the reasons for war and more about the consequences of the decision to utilize war to solve the problems of the state, including war being utilized against the state by outside forces. It appears to be so much of an afterthought that this passage appears right at the end of the twelfth chapter of thirteen and that this twelfth chapter, entitled “Incendiary Attacks,” discusses implementing fire attacks against enemy forces. Why here, of all places, he decided to write about state-level concerns in a chapter about fire attacks, we are unsure and can only speculate.

He knows that the negative aspects of war are bad for the state and the people. He talks much about winning fights before they are started and subjugating enemies without actually fighting them. By studying war and being ready to wage it to defeat any force, we may be able to determine that Sun-tzu might have viewed military capabilities and readiness as equally a deterrent to war as much as a method of winning it to achieve the objectives of the state. By showing the other states that the state of Wu, whom Sun-Tzu served, was ready to fight and win in any conflict and that all other states would best seek resolution through other means. If the state of Wu could threaten a neighboring state with war, then that neighboring state would either simply surrender to Wu’s terms or crumble in the face of a competent military force. Again, the reasons why are not necessary, only that if Wu is not always prepared for war then it could be disastrous.

The purpose of warfare, therefore, according to Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, is the preservation of the state. The military will serve as the state’s deterrent and tool of leverage against outside forces, and the reasons for war beyond that are the concern and objectives of the political body of the state. It only must be known that the political body, when choosing or not choosing war as a tool of influence, must keep the military ready and capable of fighting. That it must be preserved through competence in its leadership and through the training of its forces so that if combat were entered into, it could both win and continue to function effectively. If the military fails, for whatever reason, so too does the state.

Chanakya

Arthashastra

3rd Century BC - India

Chanakya, unknown artist depiction. From Wikimedia Commons

Mauryan Empire at one of its greatests extent. From Wikimedia Commons

The Arthashastra translates to “economics” in English but would probably be best translated contextually as “statecraft,” is a treatise developed; or at least heavily influenced by a man named Chanakya; who also goes by Vishnugupta and Kautilya. Chanakya was a political advisor and military strategist who supported Chandragupta Maurya during the latter's initial conquest of India and the establishment of the Mauryan Empire. The Mauryan conquest of India would reach its Zenith with Chandragupta’s grandson, Ashoka. Still, the foundation of that conquest, its power base, administrative guidance, and military policy would be led by Chandragupta as emperor, with Chanakya serving as his advisor and prime minister, helping him develop the methods of the Mauryan administration.

Before the establishment of the Mauryan Empire, the Nanda Empire ruled over the great kingdoms and oligarchs, the Mahajanapadas. There were 16 states in total encompassing the domain of the Nanda Empire, which in turn would be brought under control by Chandragupta over the course of around two to three years (323 - 321 BC). But the nature of the campaign against the Nanda was unclear. Chandragupta had worked to subdue the states on Nanda’s periphery before moving on to the Nanda capital, the state of Magadha, their original seat of power. He subdued the other states and foreign powers through alliances, subversion, and conflict; depending on the variables of the time.

Balancing power between states and the interests of the Maurya would play a major role in the Arthashastra. The ways by which Chanakya would assist in spreading Chandragupta’s influence and hegemony allow us to view his position on the nature of war as a tool for the pragmatic expansion of state interests instead of some ideological and righteous purpose for doing good on behalf of the general populace. At the beginning of Arthashastra’s “Book VII: The End of the Six-Fold Policy, Chapter I: The Six-Fold Policy, and Determination of Deterioration, Stagnation and Progress” it states:

The Circle of States is the source of the six-fold policy. My teacher says that peace, war, observance of neutrality, marching, alliance, and making peace with one while waging war with another are the six forms of state-policy…

Of these, agreement with pledges is peace; offensive operation is war; indifference is neutrality; making preparations is marching; seeking the protection of another is alliance; and making peace with one and waging war with another, is termed a doubly policy. These are the six forms.

Whoever is inferior to another shall make peace with him; whoever is superior in power shall wage war; whoever thinks ‘no enemy can hurt me, nor am I strong enough to destroy my enemy,’ shall observe neutrality; whoever is possessed of necessary means shall march against his enemy; whoever is devoid of necessary strength to defend himself shall seek protection of another; whoever thinks that help is necessary to work out an end shall make peace with one and wage war with another. Such is the aspect of the six forms of policy.

Of these, a wise king shall observe that form of policy which, in his opinion, enables him to build forts, to construct buildings and commercial roads, to open new plantations and villages, to exploit mines and timber and elephant forests, and at the same time to harass similar works of his enemy. (Arthashastra 368-369)

It is important for us to understand the “circle of states” or the “circle of kings'' that is mentioned at the very beginning. The rajamandala, can be translated as the “circle of kings’ states” and serves as a political theory tool for us to visualize the relationships between states. By assessing the strengths and weaknesses of one’s state when compared to the others, as well as the geographic positioning of them, Chanakya was able to suggest who should be allied, who should be made an enemy, who should be avoided, and who one should be preparing to campaign against in the future. He notes that war may not be desirable as war is often filled with uncertainty and danger but it should be used if the conditions allude that waging war would be opportune. Indeed, the nature of war is not a tool for righteous correction of wrongdoing and corruption but a form of simple arithmetic in time and space. If one’s state has greater strength than another, and the other is in a weakened position militarily and geographically, and the series of alliances is in favor of one’s nation, then war should be utilized to conquer the weaker state.

It is all about diplomacy between the various states and judging what actions a state should take in relation to the conditions of others. For example, wars are destructive in both loss of life and equipment and in the opportunity costs that the capital used for military purposes could have been used for internal development of infrastructure and boosting commerce. If one’s state is on par with a neighboring nation; neither appearing to have an advantage in either attack or defense; and neither have greater leverage through the use of allies, then this poses a good opportunity to improve the state. Later this development can then be leveraged in future conflicts as with greater capital, manufacturing, and population, a military advantage could be gained. Additionally, wars, even on a limited scale, may be utilized; alongside spies, to sabotage another state’s efforts to build up its own military and state capacity. It is all about relationships, after all; if it costs your potential enemy two or more units of silver for every unit you spend then you have a net positive in this balance of power.

Again, it will be up to the leadership to determine which policies to execute based on the environment. War, peace, neutrality, mobilization, alliance building, and strategic diplomatic maneuvering are all merely policy decisions that the king must utilize to shape and build their dynasty and kingdom. Whether or not warfare is inherently moral is irrelevant, but instead, what is moral is merely a means to influence friends, enemies, and conquered peoples.

For example, later in Book VII on the topic of acquiring land through conflict in “Chapter X: Agreement of Peace for the Acquisition of Land,” he states:

The acquisition of rich land being equal, whoever acquires such land by putting down a powerful enemy overreaches the other; for not only does he acquire territory, but also destroys an enemy and thereby augments his own power. True, there is beauty in acquiring land by putting down a weak enemy; but the land acquired will also be poor, and the king in the neighborhood who has hitherto been a friend, will now become an enemy.

The enemies being equally strong, he who acquires territory after beating a fortified enemy overreaches the other; for the capture of a fort is conducive to the protection of territory and to the destruction of wild tribes. (407)

Here, Chanakya identifies that the acquisition of land increases the power base of the conqueror. However, from whom the land is conquered has second and third-order effects. If you successfully attack and defeat a strong enemy, then you not only acquire land but also weaken the enemy in both the physical land that constitutes their base of power and the combat power of their military. However, there is caution involved with going to conquer the weak as the reason they may be weak is that their power base, the land itself, is poor, and by taking it, you will not have increased your own power sufficient enough to compensate for the enemy that you have just made and who may be leveraged against you by more powerful foes. So avoiding attacking the weak is treated not as a morally righteous thing but instead as a cost-benefit assessment.

Additionally, by securing fortresses, meaning not simply destroying them during the siege, you have the facilities necessary to then defend the very land that had just been acquired. And this acquisition of fortresses brings up another cost-benefit assessment that could be viewed as a moral decision if it wasn’t simply a pragmatic course of action. Later, in “Book XIII: Strategic Means to Capture a Fortress, Chapter IV: The Operation of a Siege,” he states:

When a fort can be captured by other means, no attempt should be made to set fire to it; for fire cannot be trusted; it not only offends gods, but also destroys the people, grains, cattle, gold, raw materials and the like. Also the acquisition of a fort with its property all destroyed is a source of further loss. (561)

Within the walls of the fort are the people, their tools, and their goods; the very things that make the land rich and will increase your power base. Fire attacks are good for breaking a siege, but Chanakya suggests that if you can secure the fortress through other means than fire, then that is the better course of action. By protecting the assets and people within the fortresses, and the fortress itself, then you gain the means to fill the coffers of the state through protecting this new taxable citizenry, as well as to immediately leverage the fortress to defend the newly acquired land. You aren’t avoiding burning the whole place down because you are a virtuous king; though you can indeed promote yourself that way to win hearts and minds, you are avoiding it because you want to protect the things you sought to conquer, the value it holds.

The purpose of war, therefore, according to Chanakya’s Arthashastra, is as a means to increase the strength of the king and dynasties. It is but one means of many available to the monarch to improve their power base, alongside other geopolitical means, such as alliances, mobilizations, and determinations of when and where to transition between war and peace. The means of war, and leniency of its use, must be weighed by the king based on what desired results they can reasonably seek to achieve. War, peace, and other forms of diplomacy are determined through a cost-benefit analysis instead of what may be viewed as right or wrong.

Aeneas Tacticus

On The Defense of Fortified Positions (Perí toú pós chrí poliorkouménous antéchein)

3rd Century BC - Greece

Relief of Aeneas the Tactician's Hydraulic Telegraph. From Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Regions of the Peloponnese. From Wikimedia Commons

Aeneas Tacticus, or Aeneas the Tactician of 3rd Century BC Greece, has some controversy as to his identity, just like most ancient authors. Some have postulated that the Aeneas who authored On the Defense Of Fortified Positions was Aeneas of Stymphalus, an Arcadian League general who fought Euphron of Sicyon. What historians have to go off of is a name, a knowledge of military affairs, and a discussion of events that, chronologically, place Aeneas Tacticus in the same time period as Aeneas of Stymphalus. It would be similar to us today discovering a document about camp discipline and sentry duties during the American Revolutionary War by someone named “Washington,” and we made the logical assumption that this individual is George Washington, Commander of the Continental Army and, later, first President of the United States.

If true, the author Aeneas Tacticus would have participated at the Battle of Mantinea (362 BC), in which, as an Arcadian, fought under the Theban commander Epaminondas and also fought alongside the Boeotian League against a coalition of Spartans, Athenians, Mantineians, and other smaller city-states under the command of Spartan King Agesilaus II. It would be a victory for the Thebans, but Epiminodas would die in the battle leading to a weaker Thebes and later the rise of Philip II of Macedon. This would lead to Phillip II’s son, Alexander the Great, establishing a short-lived Macedonian Empire.

Regardless of whether Aeneas Tacticus and Aeneas of Stymphalus are the same person or two separate individuals, Aeneas Tacticus, at least, would have been familiar with the nature of these Peloponessian conflicts and would have had a worldview congruent with an environment of constant warring between Greek city-states. Wars would occur for a short period and then cease around time for harvesting and planting; they fought in cycles around the seasons. That matters because, for Aeneas, in defense of towns and cities, the most likely aggressor would have been other Greek city-states. While the Persian invasions of Darius and Xerxes had been an existential threat in his past, other Greeks were still the most probable threat.

Of his works, most have not survived, and we only know of their existence through a reference to them in other writings. But one that has survived, this manuscript called On The Defense of Fortified Positions (Perí toú pós chrí poliorkouménous antéchein), whose literal translation is “About how they endure under siege,” discusses the topic of protecting a city or town prior and during the threat of siege from an enemy force. It is mainly about tactics, techniques, and procedures for safeguarding a town from spies and surprise attacks, maintaining a sustainable guard rotation, securing provisions, mitigating potential internal revolts, and other various points of concern in regard to a city’s defense. However, he begins the manuscript with a discussion of the importance of what he is writing, the importance of a successful defense for a Greek city-state.

In the introduction to On The Defense of Fortified Positions, Aeneas states:

When men set out from their own country to encounter strife and perils in foreign lands and some disaster befalls them by land or sea, the survivors still have their native soil, their city, and their fatherland, so that they are not all utterly destroyed. But for those who are to incur peril in defense of what they most prize, shrines and country, parents and children, and all else, the struggle is not the same nor even similar. For if they save themselves by a stout defense against the foe, their enemies will be intimidated and disinclined to attack them in the future, but if they make a poor showing in the face of danger, no hope of safety will be left. Those, therefore, who are to contend for all these precious stakes must fail in no preparation and no effort, but must take thought for many and varied activities, so that a failure may at least not seem due to their own fault. But if after all a reverse should befall them, yet at all events the survivors may some time restore their affairs to their former condition, like certain Greek peoples who, after being reduced to extremes, have re-established themselves. (On Defense of Fortified Positions, 27-29)

Aeneas does not speak about the purpose of war in the offensive though he does speak of an army on the march away from their home. He acknowledges the dangerous nature of warfare in that military forces away from home can suffer from battle and disaster to such a point they are compelled to fall back to their own lands. He doesn’t speak of why the state chooses to engage in aggressive action, just that some do. It may have been a moot discussion to him, as a manual for military and civic leaders looking at how to defend their cities wouldn’t necessarily care for the aggressor’s justifications. In defense, however, the reason is obvious and existential.

In defense of these small city-states, Greek leaders must contend with minimal strategic depth. Strategic depth is about the ability to maneuver freely and to trade space for time if necessary. Yes, the Greek city-states could maneuver on their own lands, but they were limited in what they could control. Being surrounded by numerous other city-states, unless they were allied city-states, maneuvers would have to contend with enemy counteractions. If you are Arcadian, you have the Spartans to your south, Corinth to your north, a bunch of smaller cities with various affiliations, and the Aegean Sea. If you are the Athenians, you have Corinthians to your southwest, Thebans to your northwest, and the Aegean Sea around you. Indeed, being on the Peloponnese or in any of the areas of southern Greece is extremely limiting in depth. You have your city, your lands around the city, and the rest is other Greeks and the sea; not many options for military maneuvers in the defense other than a field battle and then falling back to the city walls.

Now, the purpose of defensive warfare for Aeneas is obvious. The city itself houses everything they care about. The temples of their gods, their governing body that provides them an identity as a people, their families, and all of their worldly possessions are within the walls of their city. There is no falling back. Once the city is destroyed, that is it; therefore, to save a people, the city mustn't fall; simple enough.

Aeneas does note that defeated people can bounce back. Survivors, after having their homes destroyed and infrastructure devastated, could reoccupy what is left and attempt to rebuild what has been lost, and future generations could prosper in time. However, this is purely hopeful for a defeated people, that one day what was lost will return and vengeance will be brought upon those who destroyed it. Until destruction, however, the best option to save a people is a “stout defense” to defeat the aggressor. On The Defense of Fortified Positions gives guidance on how to create that stout defense.

While Aeneas focuses on an aspect of defensive war, his feelings about its importance, and his argument for why the defense of the city is so critical a topic, this may allow us to speculate on his view of offensive war. This is a purely speculative position, but; if the defense is so existential to a people; if being attacked in your own lands amongst your homes and family is so dangerous; if you are one lost battle away from the enemy banging on the city gates, then going on the offensive may be the best option. As the saying goes, “the best defense is a good offense,” which may suit the Greek city-states very well. Bringing the horrors of war to our adversary’s city walls is a better option than waiting for them to do the same to us.

The purpose of warfare, therefore, from the perspective of Aeneas Tacticus in On the Defense of Fortified Positions, is one of defending one’s people and their way of life. This could extend to offensive actions being taken preemptively to avoid fighting the defensive. Still, regardless, we know from the writings we have from Aeneas his perspective on what would happen if you failed to defend your city. This threat justifies the study and discussion of defending cities that his writing goes on to do.

Onasander

The General (Strategikos)

1st Century AD - Greece

"Last Day on Corinth" by Tony Robert-Fleury, 1870. Depicts the sack of Corinth by the Romans have the Battle of Corinth in 157 BC. This would being the age of Roman control of Greece, and occurred two-hundred years prior to Onasander.

Roman conquest of Britain. Strategikos was dedicated to Quintus Varanus, who led the command into Wales (pink arrrows). From Wikimedia Commons

Not much is known of Onasander, even the correct spelling of his name amongst students of Ancient Greek works. Still, we know that he was a 1st-century AD Greek Platonic philosopher. He allegedly even wrote a commentary on Plato’s Republic, which has been lost to history. His name has been tied to the same Onasander that wrote this treatise, Strategikos, which translates as “strategic.” However, this work also goes by the title, The General, since it covers mostly the duties and desirable attributes of good generals.

Onasander dedicated this work to a Roman consul, Quintus Veranius, who would eventually become governor of Britain in 57 AD and died a year or two later. As a result, Strategikos was probably written at some point within the ’50s of the 1st Millennium. A lot occurred for the Greeks between Aeneas Tacticus’ On The Defence of Fortified Positions and Onasander’s Strategikos. By 146 BC, Rome had conquered Greece. A hundred years later, in 49 BC, Gaius Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon. In 27 BC, the Roman Republic made way for the Roman Empire under Octavian. The Roman conquest of Britain occurred in 43 BC. Then in 54 BC, Emperor Nero ordered Veranius to continue military operations on the island, where he focused on operations in the territory of modern-day Wales.

By this time, the Greeks would have experienced around two-hundred years of Roman rule. There would be devastation in portions of Greece due to a Greek rebellion of 88 BC and the Roman civil war of 49-45 BC. The Roman Empire would then invest heavily to rebuild Greek cities, and by the time of Onasander, there was much cultural exchange between these two peoples. Basically, lived in a world where his people were ruled by a foreign power that had initially been oppressive but who had eased their rule and even enriched Greek communities for around eighty years by the time of this work’s publishing.

Naturally, Greeks participating in Roman conquests would be auxiliary elements to Roman legions if they were not citizens. We could speculate the reasons for why Onasander would have provided his thoughts on generalship. One possibility could include success on the battlefield and expanding the Roman Empire, which would also economically improve the conditions for Greece. A second possibility is that Greeks were serving under Roman commanders, and by ensuring Roman success, he could safeguard his countrymen who served with them. A third possibility is that he could have had respect or appreciation for Rome and wanted to support them for that sake alone. And a fourth possibility is that he could have simply had the desire to discuss his thoughts on military theory and wanted to share it with notable Romans currently engaged in military operations. It also could have been a combination of any of these possibilities.

Regardless of the reasons for writing Strategikos, he does provide us with an indirect perspective of the purpose of war by discussing that there are both just and unjust wars. In the chapter “The Necessity of a Reasonable Cause for War,'' he states:

The causes of war, I believe, should be marshaled with the greatest of care; it should be evident to all that one fights on the side of justice. For then the gods also, kindly disposed, become comrades in arms to the soldiers, and men are more eager to take their stand against the foe. For with the knowledge that they are not fighting an aggressive but a defensive war, with consciences free from evil design, they contribute a courage that is complete; while those who believe an unjust war is displeasing to heaven, because of this very opinion enter the war with fear, even if they are not about to face danger at the hands of the enemy. On this account the general must first announce, by speeches and through embassies, what he wishes to obtain and what he is not willing to concede, in order that it may appear that, because the enemy will not agree to his reasonable demand, it is of necessity, not by his own preference, that he is taking the field. (Strategikos, 391)

The first element of this passage discusses the nature of just and unjust conflict in its impact on the morale of the warring parties. While the purpose of war may not be stated, we know that it must be viewed as just. What makes it just is left up to the reader's interpretation, and more importantly, it is the general whose charisma, rationale, oratory, and literary skill needs to justify the conflict to their warriors and the public.

Intelligent leaders on both sides of a conflict will latch on to justifications for their righteousness in the fight. For example, the aggressor might justify going to war as punishment and revenge for a previous violation. The defender will naturally justify its actions in the war as a defense of their homes and territory. Defenders, naturally, just as Aeneas would attest, have the justification of protecting everything they love. Even if the defenders were the previous aggressors and may now be facing a justified retaliation, they aren’t going to give up and accept whatever may come; they will fight to protect their homes, families, and people.

The aggressors, however, have to find some purpose to latch onto to justify their actions. Using the five factors of human violence proposed by Steven Pinker in The Better Angels of Our Nature and which we discussed in Chapter 2.0: On Violence, we can see some of the forms of justifications used for offensive warfare. Some examples within the five factors that could justify aggressive war include:

- Predation: Conquering land for resources

- Domination: Defeating and enslaving lesser tribes; taking key terrain for better strategic positions; forcing lesser peoples to provide periodic tribute; incorporating people into a greater empire.

- Revenge: Destroying an enemy military and its people for a past violation; raping and pillaging in response to similar enemy action; inspiring awe and terror to deter future violations.

- Sadism: Raping and slaughtering because the culture promotes it, capturing slaves for torture or sexual subordination.

- Ideology: Waging religious conflicts like Crusades/Jihads; defeating an ideological foe as a requirement of one’s beliefs; a religious or historical claim to lands; fighting and killing because “that is what the gods want.”

Additionally, let’s look at that discussion of the impact of the gods upon the beliefs of the fighters. While he mentions that the gods become “comrades in arms,” this thought of divine support is more important in its impact on morale than in the belief that Ares/Mars will join in fighting Greco-Roman enemies. The belief in the soldiers that the gods support them is a powerful motivator, while the inverse is a great demotivator. If justified, a setback could be chalked up to a test of mettle that they must overcome. If not justified, a setback could appear to be a curse by the gods.

The second element of justification comes from exhausting other courses of action before waging conflict. The effort to negotiate for terms with an adversary, to gain the purpose of war without actually waging it and contributing to the world’s suffering, is seen as a necessary step to ensure that the subsequent waging of war is just. In a way, it tells the world, “we tried peace; now we are only left with one option” thus, with a justification, the support of gods, and exhausting all other avenues, Onasander finds the purpose of the war to be just.

The purpose of warfare, therefore, for Onasander in Strategikos is to accomplish the objectives of the state, whatever they may be. However, it must be done justifiedly and as a last resort.

Zhuge Liang

Facilitation and Appropriateness (Bien Yi)

3rd Century AD - Three Kingdoms China

Zhuge Liang as depicted in Romance of the Three Kingdoms XIV from Koei-Tecmo

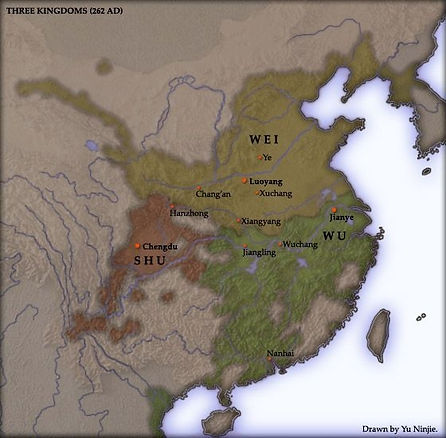

Map of the Three Kingdoms (262 AD) prior to the successful invasion of Shu by Wei. Pulled from Wikimedia Commons, drawn by Yu Ninjie

Zhuge Liang has been a popular Chinese historical individual even into contemporary times. Whereas Sun-Tzu is famous for his writing The Art of War, and only a few know of his contributions to the state of Wu, it is the reverse for Zhuge Liang. Zhuge Liang is known for his contributions to the rise and establishment of the Shu-Han Dynasty during the tumultuous and highly romanticized Three Kingdoms period (220-280 AD) at the close of the Later Han dynasty (23-220 AD).

Like much of Chinese history, the central authority of the Han would weaken as a result of court infighting, the Yellow Turban Rebellion, and the control of the child emperor under the warlord Dong Zhou. This chaos throughout China allowed more warlords to claim their power bases to stabilize their people and reaffirm the strength and nobility of their station. One warlord, the imperial uncle Liu Bei, sought out Zhuge Liang to be his advisor. Together they would eventually create the short-lived state of Shu, which would become Shu-Han, to reaffirm their authority over the lost Han imperial line to which Liu Bei is related - allegedly.

In popular culture, much of the story of Zhuge Liang is taken from The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a historical novel by Luo Guanzhong in the 14th Century AD in Ming Dynasty China. However, the novel, and much of our knowledge of the Three Kingdoms period, comes from the Records of the Three Kingdoms written during the 3rd Century AD by Chen Shou - note that no complete English translation exists, yet. It is the closest thing we have to a primary source of biographies and narratives telling us what occurred during this time.

These collections of writings attributed to Zhuge Liang, the Jiang Yuan and the Bien Yi, to the best efforts of the translator, are called “compilations on generalship” and “facilitation and appropriateness” in English. They provide Zhuge Liang’s perspectives on particular actions and attitudes of civil servants and generals. And while in his writing, he does mention many concepts associated with Confucianism and Taoism; he also has a strong Legalist take on the conduct of affairs. This means that while he discusses the importance of concepts such as benevolence, virtuous behavior, filial piety, and the underlying belief that there is a Tao of Heaven and Man, he is also a staunch adherent to the law. He is much more likely to behead you than pardon you if you break the law where the punishment requires beheading, regardless of your relationships or past actions. The law is the law, and potentially not carrying out punishments where the law requires could be disharmonious to a society that is structured around laws.

All that being said, what you need to know about the environment that Zhuge Liang lived in is this:

- The Han was weak, and there were wars throughout the lands.

- Liu Bei convinced Zhuge Liang to enter his service in his attempts to restore the Han.

- Zhuge Liang assisted Liu Bei in establishing a power base in Yi, modern-day Sichuan, and Chongqing provinces.

- Zhuge Liang helped compel Liu Bei to assume the position of Emperor of the short-lived Shu-Han Dynasty.

- Zhuge Liang’s position as the Prime Minister of Shu-Han helped Liu Bei, and his son, Liu Shan, hold off the kingdoms (dynasties) of Wei and Wu.

- And at some point during his advisory position to Liu Family, he wrote the passages of the Jiang Yuan and Bien Yi.

So, in regards to the purpose of warfare in a time of great chaos, that is the Three Kingdoms period, Zhuge Liang wrote in Chapter 9 of the Bien Yi:

Governmental measures for “administering the army” refer to governing border affairs. The Tao for correcting chaos and preserving the state is to adopt awesome martial measures. Executing the brutal and conducting punitive expeditions against the contrary is the way to preserve the state and bring security to the altars of soil. For this reason, even when civil affairs prevail you must make military preparations.

All living beings with blood, even insects, invariably have claws and fangs that they can employ. When happy they play together, when angry they harm each other. People lack claws and fangs so they created weapons and armor in order to aid their defense. Thus the army assists the state and ministers assist the ruler. When their support is strong the state will be secure but when weak the state will be endangered. It all lies in who is entrusted with responsibility for command. If they are not generals for the people and assistants for the state, they will not master the army. Therefore, in governing, the state is administered with the civil, but in controlling the army the plans must be martial. Governing the state must react to the exterior, controlling the army must accord with the interior. (Bien Yi, 234)

Zhuge Liang harkens back to the historical precedent that when there is suffering and chaos when there is disharmony in the world, previous virtuous rulers have used the tool of war to set things right. In his writings on state matters, many of his concepts were shaped by Jiang Ziya’s Liu Tao and the Ssu-ma fa of the state of Qi. Naturally, well-known scholarly works would be the basis on which a person becomes a learned individual. Being able to quote passages from important civil and military treatises was a method of meritocratic testing for civil service posts in governance and an informal way to gauge a person’s intelligence.

In peace, when promoting civil matters, such as facilitating the development of agriculture, infrastructure, and trade, the state must also not forget to maintain a ready military capability. The reason for this, as he begins his second passage, is that a natural state of violence exists amongst humans. He likens human interactions in much the same way as other creatures in that animals can both play and fight with each other depending on their emotions at the time. However, the difference between humans and the other animals is that humans “created weapons,” whereas the animals were born with their “claws and fangs.”